How could ancient Persian science have grasped the principles of electricity and arrived at this knowledge?

Biblical clues

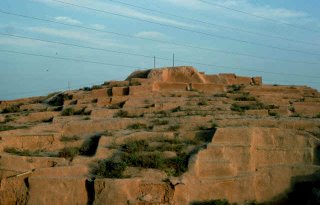

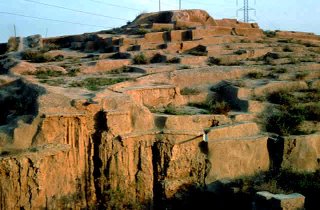

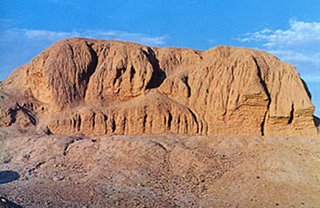

It was in 1938, while working in Khujut Rabu, just outside Baghdad in modern day Iraq, that German archaeologist Wilhelm Konig unearthed a five-inch-long (13 cm) clay jar containing a copper cylinder that encased an iron rod.

Batteries dated to around 200 BC

Could have been used in gilding

The vessel showed signs of corrosion, and early tests revealed that an acidic agent, such as vinegar or wine had been present.

In the early 1900s, many European archaeologists were excavating ancient Mesopotamian sites, looking for evidence of Biblical tales like the Tree of Knowledge and Noah's flood.

Konig did not waste his time finding alternative explanations for his discovery. To him, it had to have been a battery.

Though this was hard to explain, and did not sit comfortably with the religious ideology of the time, he published his conclusions. But soon the world was at war, and his discovery was forgotten.

Scientific awareness

More than 60 years after their discovery, the batteries of Baghdad - as there are perhaps a dozen of them - are shrouded in myth.

"The batteries have always attracted interest as curios," says Dr Paul Craddock, a metallurgy expert of the ancient Near East from the British Museum.

"They are a one-off. As far as we know, nobody else has found anything like these. They are odd things; they are one of life's enigmas."

No two accounts of them are the same. Some say the batteries were excavated, others that Konig found them in the basement of the Baghdad Museum when he took over as director. There is no definite figure on how many have been found, and their age is disputed.

Most sources date the batteries to around 200 BC - in the Parthian era, circa 250 BC to AD 225. Skilled warriors, the Parthians were not noted for their scientific achievements.

"Although this collection of objects is usually dated as Parthian, the grounds for this are unclear," says Dr St John Simpson, also from the department of the ancient Near East at the British Museum.

"The pot itself is Sassanian. This discrepancy presumably lies either in a misidentification of the age of the ceramic vessel, or the site at which they were found."

Underlying principles

In the history of the Middle East, the Sassanian period (circa AD 225 - 640) marks the end of the ancient and the beginning of the more scientific medieval era.

Though most archaeologists agree the devices were batteries, there is much conjecture as to how they could have been discovered, and what they were used for.

How could ancient Persian science have grasped the principles of electricity and arrived at this knowledge?

Perhaps they did not. Many inventions are conceived before the underlying principles are properly understood.

The Chinese invented gunpowder long before the principles of combustion were deduced, and the rediscovery of old herbal medicines is now a common occurrence.

You do not always have to understand why something works - just that it does.

Enough zap

It is certain the Baghdad batteries could conduct an electric current because many replicas have been made, including by students of ancient history under the direction of Dr Marjorie Senechal, professor of the history of science and technology, Smith College, US.

"I don't think anyone can say for sure what they were used for, but they may have been batteries because they do work," she says. Replicas can produce voltages from 0.8 to nearly two volts.

Making an electric current requires two metals with different electro potentials and an ion carrying solution, known as an electrolyte, to ferry the electrons between them.

Connected in series, a set of batteries could theoretically produce a much higher voltage, though no wires have ever been found that would prove this had been the case.

"It's a pity we have not found any wires," says Dr Craddock. "It means our interpretation of them could be completely wrong."

But he is sure the objects are batteries and that there could be more of them to discover. "Other examples may exist that lie in museums elsewhere unrecognised".

He says this is especially possible if any items are missing, as the objects only look like batteries when all the pieces are in place.

Possible uses

Some have suggested the batteries may have been used medicinally.

The ancient Greeks wrote of the pain killing effect of electric fish when applied to the soles of the feet.

The Chinese had developed acupuncture by this time, and still use acupuncture combined with an electric current. This may explain the presence of needle-like objects found with some of the batteries.

But this tiny voltage would surely have been ineffective against real pain, considering the well-recorded use of other painkillers in the ancient world like cannabis, opium and wine.

Other scientists believe the batteries were used for electroplating - transferring a thin layer of metal on to another metal surface - a technique still used today and a common classroom experiment.

This idea is appealing because at its core lies the mother of many inventions: money.

In the making of jewellery, for example, a layer of gold or silver is often applied to enhance its beauty in a process called gilding.

Grape electrolyte

Two main techniques of gilding were used at the time and are still in use today: hammering the precious metal into thin strips using brute force, or mixing it with a mercury base which is then pasted over the article.

These techniques are effective, but wasteful compared with the addition of a small but consistent layer of metal by electro-deposition. The ability to mysteriously electroplate gold or silver on to such objects would not only save precious resources and money, but could also win you important friends at court.

Let's hope the world manages to resolve its present problems so people can go and see them

Dr Paul Craddock A palace, kingdom, or even the sultan's daughter may have been the reward for such knowledge - and motivation to keep it secret.

Testing this idea in the late seventies, Dr Arne Eggebrecht, then director of Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum in Hildesheim, connected many replica Baghdad batteries together using grape juice as an electrolyte, and claimed to have deposited a thin layer of silver on to another surface, just one ten thousandth of a millimetre thick.

Other researchers though, have disputed these results and have been unable to replicate them.

"There does not exist any written documentation of the experiments which took place here in 1978," says Dr Bettina Schmitz, currently a researcher based at the same Roemer and Pelizaeus Museum.

"The experiments weren't even documented by photos, which really is a pity," she says. "I have searched through the archives of this museum and I talked to everyone involved in 1978 with no results."

Tingling idols

Although a larger voltage can be obtained by connecting more than one battery together, it is the ampage which is the real limiting factor, and many doubt whether a high enough power could ever have been obtained, even from tens of Baghdad batteries.

One serious flaw with the electroplating hypothesis is the lack of items from this place and time that have been treated in this way.

"The examples we see from this region and era are conventional gild plating and mercury gilding," says Dr Craddock. "There's never been any untouchable evidence to support the electroplating theory."

He suggests a cluster of the batteries, connected in parallel, may have been hidden inside a metal statue or idol.

He thinks that anyone touching this statue may have received a tiny but noticeable electric shock, something akin to the static discharge that can infect offices, equipment and children's parties.

"I have always suspected you would get tricks done in the temple," says Dr Craddock. "The statue of a god could be wired up and then the priest would ask you questions.

"If you gave the wrong answer, you'd touch the statue and would get a minor shock along with perhaps a small mysterious blue flash of light. Get the answer right, and the trickster or priest could disconnect the batteries and no shock would arrive - the person would then be convinced of the power of the statue, priest and the religion."

Magical rituals

It is said that to the uninitiated, science cannot be distinguished from magic. "In Egypt we know this sort of thing happened with Hero's engine," Dr Craddock says.

Hero's engine was a primitive steam-driven machine, and like the battery of Baghdad, no one is quite sure what it was used for, but are convinced it could work.

If this idol could be found, it would be strong evidence to support the new theory. With the batteries inside, was this object once revered, like the Oracle of Delphi in Greece, and "charged" with godly powers?

Even if the current were insufficient to provide a genuine shock, it may have felt warm, a bizarre tingle to the touch of the unsuspecting finger.

At the very least, it could have just been the container of these articles, to keep their secret safe.

Perhaps it is too early to say the battery has been convincingly demonstrated to be part of a magical ritual. Further examination, including accurate dating, of the batteries' components are needed to really answer this mystery.

No one knows if such an idol or statue that could have hidden the batteries really exists, but perhaps the opportunity to look is not too far away - if the items survive the looming war in the Middle East.

"These objects belong to the successors of the people who made them," says Dr Craddock. "Let's hope the world manages to resolve its present problems so people can go and see them."